James Webb Space Telescope Peers Into a Star’s Final Dance, Captures Four Dust Shells

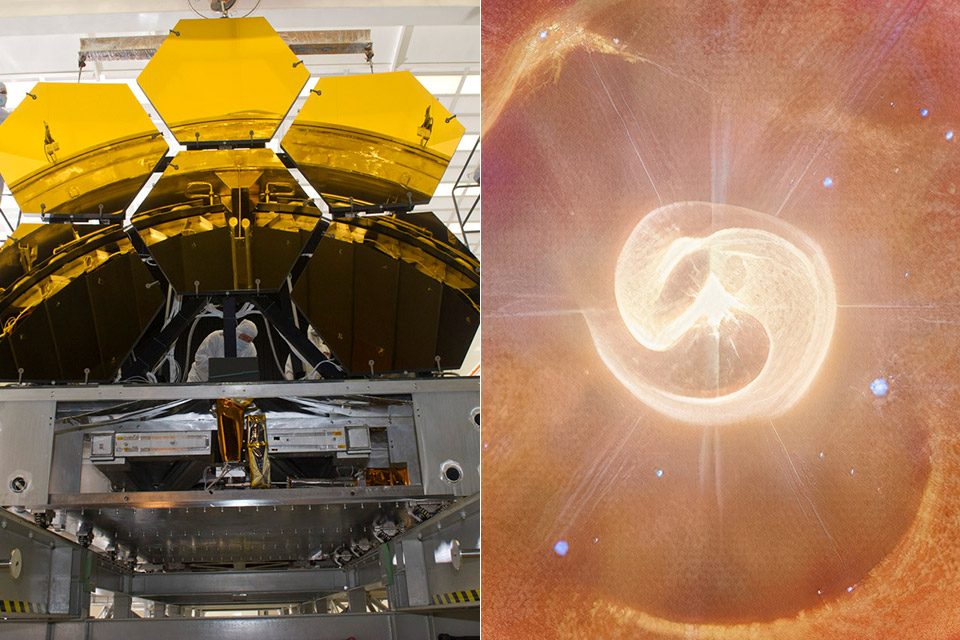

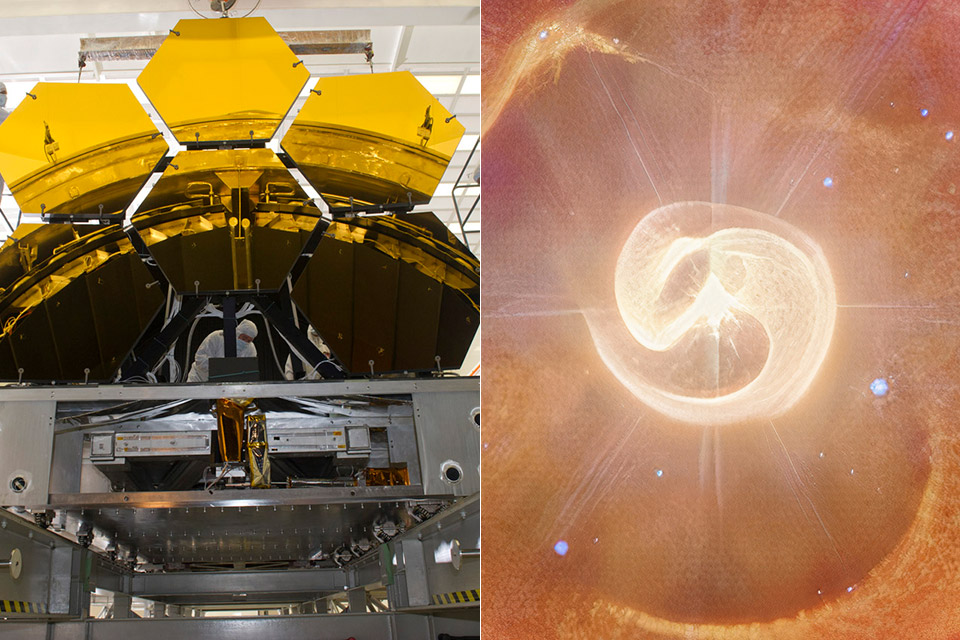

Astronomers have long been searching for the faint lights of dying stars, those huge, short-lived fireballs that blaze brightly before fading away into the galaxy’s dark corners. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has now given us a look inside one such system, Apep, a trio of stars 8,000 light years away in a long, agonizing waltz. This mid-infrared image is raw and unprocessed, showing four shells of carbon dust spiraling outward in a tangled mess like an unraveled rope.

The Apep system has two Wolf-Rayet stars in a tight, star-hugging binary. These are the heavy hitters of the universe, once giant gasbags dozens of times bigger than our sun, now stripped down to their cores and blazing with fury. Their surfaces generate hurricane-force winds of up to 2,000 miles per second, blowing material into space in huge, relentless blows. With a third companion, a supergiant that has retained some of its bulk, the system sometimes spits out dust. Every 190 years or so the Wolf-Rayet duo gets close enough that their winds collide, creating clouds of carbon dust that leave trails and glow in the infrared. Over the past seven centuries or so these collisions have built up the four shells, each one a tiny snapshot of a past encounter, slowly expanding into nothing.

Webb’s mid-infrared instrument caught the scene in great detail, detecting the heat of the dust that other telescopes would miss. Ground-based telescopes, like the Very Large Telescope in Chile, caught a glimpse of the innermost shell a few years ago but it was all a bit fuzzy and vague. The researchers combined this new data with 8 years of measurements of how fast the shells are expanding to get a handle on the orbit and confirm that the stars’ near-misses every 25 years are what’s driving this dust factory.

Each shell is a chapter in Apep’s story, with the innermost curving like a reverse lowercase e, dense and bright against the darkness, and the next three spiraling outward, their arms getting shorter as they go. Carbon is the main element, in an amorphous form that retains heat longer than silicates so the glow lasts for light-years. The supergiant, farther out, plows through these expanding rings, scooping up V-shaped gaps from 10 o’clock to 2 o’clock on the image. These cavities show the third star’s connection to the system by bending the dust into funnels that trace its path.

This is a critical time for Apep because the Wolf-Rayet stars are nearing the end of their lives as supernovae that can produce gamma-ray bursts, those dazzling lights that can outshine entire galaxies for seconds. When they go, black holes may form and suck up the leftovers at the center of the system. But before the explosion, the dust they make enriches the galaxy by providing raw material for future stars and planets. Apep is the only known binary in our Milky Way with only a thousand Wolf-Rayet stars in its disk. Its 190-year cycle is much longer than others, like the 30-year loop in similar systems, so we get a unique view into how long-term orbits affect these final acts.

James Webb Space Telescope Peers Into a Star’s Final Dance, Captures Four Dust Shells

#James #Webb #Space #Telescope #Peers #Stars #Final #Dance #Captures #Dust #Shells